In Defense of Bullet-Biting

Any serious thinker has to do it sometimes.

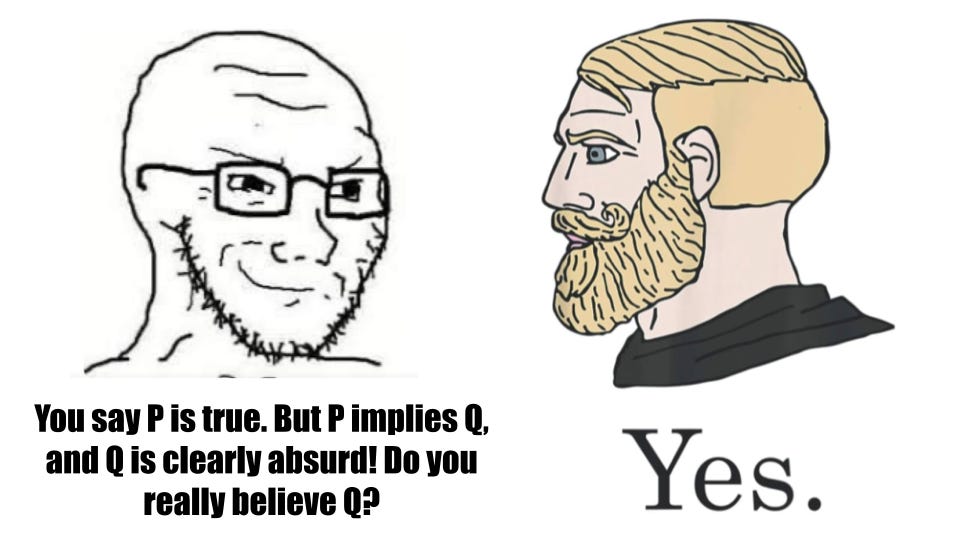

One of the most famous logical techniques is known as reductio ad absurdum. This is the technique where you disprove a statement by proving that it leads to false or absurd conclusions. If somebody pulls a reductio ad absurdum on you, you have two options: You can either admit that you were wrong, or you can pull a Chad.

Biting the bullet — admitting that a counterintuitive or absurd-sounding conclusion is actually true — can be very fun. It’s the rhetorical equivalent of a judo chop. Your opponent spent all this time teeing up the perfect argument against your position, and all you have to say in response is “Yes.”

How much you choose to bite the bullet is largely a matter of personality and temperament. Some people (especially if they’re more agreeable) are squeamish about admitting things that sound strange or socially taboo. Other people (especially if they’re more disagreeable) have no such reservations, and if anything take pleasure in going against the grain. Utilitarians are famous in philosophy circles for our tendency to frequently bite bullets. We will accept any bizarre conclusion before rejecting our utilitarian premise — up to and including the idea that humans should spend significant resources to promote shrimp welfare.

I freely admit that my utilitarian philosophy commits me to some very strange beliefs. You can ask me, “If you knew for certain that X promotes utility, would you support X?” I’ll say yes every time, without hesitation. X could be literally anything. X could be child murder, and I would still support it if I knew for sure that it would maximize utility.

Some people will hear that and automatically take it as a disproof of utilitarianism. “Child murder is so obviously evil,” they’d contend, “that no sane ideology could justify it, even in principle. Therefore, utilitarianism must be wrong.” But this would be the wrong conclusion, for two reasons:

First, false premises lead to false conclusions. If I began with the false premise that 2+2=5, then I could easily prove the false conclusion that I am the king of England.1 Similarly, if you start with an insane premise like “Child murder promotes utility” then of course you can draw insane conclusions from that. In the real world, child murder is actually extremely bad for utility! It’s bad for the child itself (who misses out on the positive utility from the life they could have lived) as well as the community around the child (which receives negative utility from the loss of their child). You can cook up any strange premise you want in thought-experiment la-la-land, but here on planet Earth, utilitarians don’t support child murder.

Second, it’s not just utilitarianism. Most ideologies, if they are being consistent, are obligated to bite bullets just as big as “Child murder can be justified”. Consider:

If you take religion seriously, then you probably believe that you are obligated to be obedient to God. So, if God tells you to sacrifice your only son, then you are obligated to do it. Thus, religious people must believe that child murder is justified in at least some circumstances.

If you believe in just war theory, then you believe that it is sometimes permissible for a country to go to war. But war involves a lot of child-killing! Even the most moral armies in the world generally can’t avoid killing a few kids as collateral damage, so anybody advocating war is ipso facto advocating for limited child murder. Thus, unless you believe in absolute pacifism, you must believe that child murder is justified in at least some circumstances.

Let’s say you believe in egalitarianism — the idea that all people are equal in inherent dignity, regardless of their personal characteristics. Then, you must believe that child murderers have equal dignity to the children they’re murdering.

Religion, just war theory, and egalitarianism are all commonly-held, “common sense” belief systems, yet each of them leads to conclusions just as strange as the ones I derive from utilitarianism.

Anybody who has studied mathematics knows that with just a few starting axioms, you can prove a surprisingly wide range of theorems. In Euclidian geometry, for instance, we start off with just five axioms, and then use them to prove all the known facts of the geometric world. The idea that the sum of angles of any triangle always adds up to exactly 180° is pretty counterintuitive, but it follows logically from simple premises. And so it is with moral philosophy. You can start with a set of modest, highly intuitive moral axioms, and end up with a set of extreme, highly counterintuitive conclusions.

I suppose you could avoid this by abandoning the idea of logical consistency entirely. Maybe you believe that formal logic is the domain of philosophy autists, and instead, people should form their moral beliefs via some combination of gut feelings and vague heuristics. (Indeed, this is how most people form their beliefs, whether or not they’re self-aware enough to admit it.) That way, if your gut tells you that something is wrong, you can simply reject it without having to do the work of making that rejection consistent with your other beliefs. No bullet-biting necessary! I have nothing against this approach, but I will note: Admitting that your ideology is emotion-driven and logically inconsistent is itself biting a pretty big bullet.

Assuming you do care about logical consistency, there’s really no way to avoid the fact that your beliefs probably have weird implications. While utilitarians like myself are the most visible in our bullet-biting, we are by no means alone. Every ideology breaks down when applied to weird edge cases, and whatever beliefs you hold, I can probably design a thought experiment to make you look like a psychopath. No matter what premises you start with, you’ll have to bite the bullet eventually.

Starting with 2+2=5, we subtract 2 from both sides to obtain 2=3. Then we subtract another 1 from each side to obtain 1=2. The king of England is a man, and so am I. That makes 2 men. But since we know that 1=2, we are really 1 man. Therefore, I am the king of England.

I think utilitarianism can be useful, but I’m not persuaded by the bullet-biting impulse.

This is chiefly because the actual test of ethics *is* emotional and heuristic. There’s no scoresheet to check against; the universe does not indicate its displeasure with our moral choices, except insofar as we, collectively and/or individually, are displeased by them.

The George Box quote: “All models are wrong, some are useful” captures some of the risk of unnecessary bullet biting. Consider two analogs from physics.

1. While working on the laws of electromagnetism, James Clerk Maxwell realized the math would only work if he added a term to one of the equations, which he called displacement current. Bullet biting for the win: this term, born out of a purely logical necessity (Maxwell’s laws, like Newton’s, are wrong, but much better than what we had before), was experimentally validated and allowed for the unification of electromagnetism and optics.

2. Newton’s laws of motion are a staggering achievement; it’s basically impossible to overstate their impact on physics, and on the world more broadly. They’re also wrong, in ways that became apparent through use. It breaks down for systems that are extremal, e.g. very large, very small, or very fast. Rather than “biting the Newtonian bullet,” quantum mechanics and the special and general theory of relativity were developed and experimentally tested, which resolved many of the issues in Newton’s laws, while leaving some blanks and open problems.

What’s key in both examples is that it’s our ability to test the theories that makes biting the bullet a good/or bad choice. You cannot actually quantify and validate a “util” without some prior aesthetic and emotional commitment; there’s no Michelson-Morley experiment to run to show the absence of ethical aether.

So I’ll keep utilitarian calculus in the toolbox for reasonably well-defined scenarios, like setting Pigouvian taxes, but I won’t worry much when I get absurd results out of it either (e.g. Bentham’s Bulldog’s belief that bees would be better off dead)

Would you kill your family to save 5 Chinese billionaires? 😂